Jaguar World August 2022 History – Marathon Men

HISTORY – Marathon Men

In August 1952, four racing drivers used an XK120 fixedhead coupe for seven days and seven nights at the french circuit of Montlhéry to break several average speed records. To mark the 70th anniversary of the event, we take a closer look at their achievements.

“IT WAS impossible to keep one’s mind occupied on a job like that,” wrote (Sir) Stirling Moss in his 1987 autography, My Cars, My Career. “We had a two-way radio which helped keep boredom at bay. We talked all the time, called each other names, even told stories.”

Words: Paul Walton Archive Images: Jaguar Heritage

Moss could easily have been talking about one of Jaguar’s early Le Mans victories or any other long-distance race, but it was actually a unique endurance event from 1952, when he and three others drove a largely standard XK120 for seven days and nights to set several distance records. Completed at the banked 1.35 mile oval circuit of L’autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry, 15 miles south of Paris, the week-long marathon illustrated the reliability of a Jaguar arguably more than any race could ever do.

The stunt was the idea of racing driver, Leslie Johnson, who had won the XK120’s inaugural event at Silverstone in 1949 before finishing fifth on the Mille Miglia a year later. This wouldn’t be the first time Johnson had undertaken a long-distance run; in September he and Jaguar’s then-new signing, the 21-year-old Stirling Moss, drove the same alloy-bodied XK120 he’d used for the Mille Miglia, JWK 651, for 24 hours on the L’autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry oval circuit. Although their target was an average of 100 mph, they actually achieved 107.46 mph. Johnson returned to Montlhéry the following year with the same car to set a new one-hour record of 131.83 mph.

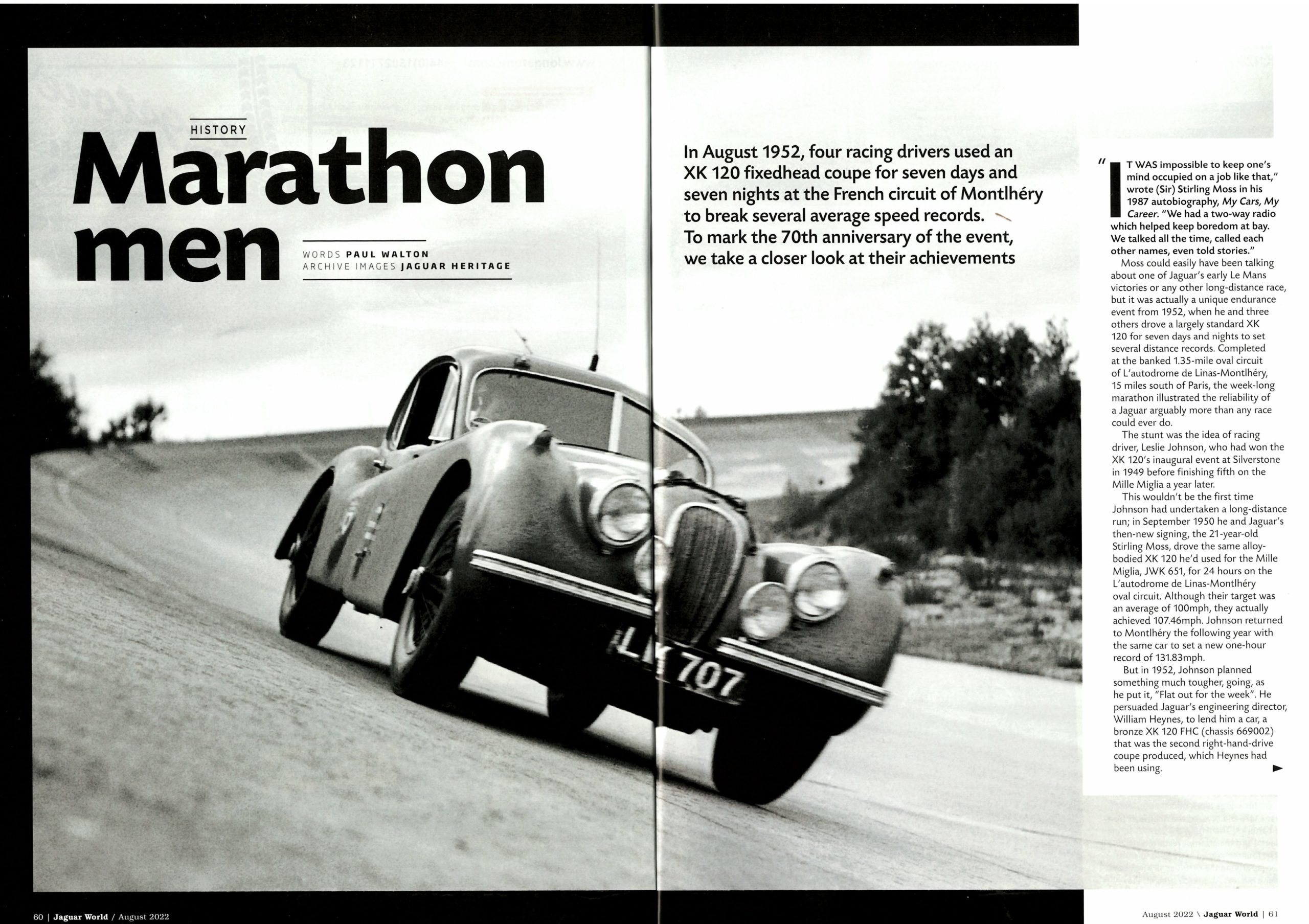

But in 1952, Johnson planned something much tougher, going, as he put it “Flat out for the week”. He persuaded Jaguar’s engineering director, William Heynes, to lend him a car, a bronze XK120 FHC (chassis 669002) that was the second right-hand-drive coupe produce, which heynes had been using.

Registered LWK 707, it was uprated with a two-way Pye radio, long-range petrol tanks, a quick-release fuel filler cap, two under-bonnet lamps (including one pointed at the dipstick), a larger sump plus an additional windscreen wiper to improve visibility on the banking. It also featured the optional 2.27:1 final drive ratio for sustained high speed plus wire wheels from the Special Equipment model to help with brake cooling.

The engine, though, was remarkably standard. Numbered W44411-8, its capacity and compression remained unchanged at 3,442 cc and 8:1 respectively. The carburettors were production-type H6 items with AC ‘pancake’ filters and the head was standard. Bar the fitting of competition-type cams, the only other changes were that the main and big-end bearings were lead indium and that Brico C-type solid-skirt pistons were fitted. On the test bench, the engine’s maximum power was 175.5 bhp at 5,000 rpm.

Following the 24-hour event in 1950, Moss was keen to take part once again. “I thought it was rather a fund thing to do,” he told me during a 2008 interview, “and not something you do every day in your career. I also thought it would be a tremendous achievement for a British car.”

As well as Moss, Johnson got two other Jaguar drivers involved including Bert Hadley – who had been his 1950 Le Mans co-driver – plus Jack Fairman who had shared Moss’s C-Type at le Mans the following year.

The attempt took place in August 1952 but didn’t get off to a great start when the car hit a large block of concrete, which burst a tyre and severed the main lead from the batteries. Thankfully, the car was soon repaired and the attempt restarted.

The four men drove in three-hour shifts and a lap around the circuit at 120 mph took under a minute. After each straight, they would hit the 30-degree banking high up, near the lip before plunging down again for the following straight. It was, as Moss said in his 1987 autobiography, quite the strain, “One dare not let the mind wander, because we were running within four feet of the banking at around 120 mph. I worked out how many million revs the engine made in a day, how many times the wheels turned, things like that.”

Yet the 22-year-old still had time to spot what he thought was a pretty girl on the side of the track. “Every time I completed a lap and drove past I blew her a kiss,” continued Moss in 2008. “But when I came in after my shift, I discovered she was not actually that pretty. It’s funny how different things look at 100 mph!”

The speed and dangerous nature of the track aside, it wasn’t an easy experience for the drivers. Moss told me that with it being France in August, the XK120’s cabin became stiflingly hot during the day but freezing cold at night.

Visibility in the dark was also an issue. Due to not wanting to drain the battery, the drivers couldn’t use the extra lights, meaning the main beam had to be set high so they could see over the top of the banking. This resulted in not being able to see a thing on the straights and so they hit several hares, rabbits and birds.

Leslie also reckoned he saw a huge, ten foot figure wearing a long cloak and a tall, pointed hat striding towards him along the verge. “It worried the life out of him for the rest of his stint,” wrote Moss. In reality, it was Stirling sitting on Jack Fairman’s shoulders with a tarpaulin wrapped around him and a fuel filler on his head. “All very childish,” admitted Moss in his book, “but good fun in the circumstances.”

Johnson later got his own back during one of Moss’s stints. “I came whistling off the banking to find him sitting with jack Fairman in the middle of the track playing cards!” He also put the pit board out on the track so that Moss’s natural line past the pits put him between it and the timekeeper’s hut. When Moss zoomed past, Johnson was casually lounging beside the hut in a deckchair so Moss gave him a wave and shot between the gap. On subsequent laps, Johnson moved the board ever close to the hut, meaning the gap Moss had to pass through became smaller and smaller. It was Johnson who gave in first, eventually putting the board back into its proper position in the hut. As Moss wrote years later, “At least it passed the time.”

Yet despite these antics, the car plodded on relentlessly with no issues. By averaging an incredible 107.31 mph, the team smashed the average speed over 10,000 km, a record that had stood in international Class C (3,000 cc to 5,000 cc) since 1934. They also set a new world record for an average speed over three days at 105.55 mph. These were quickly followed by the 15,000 kilometre (101.95 mph), 10,000 miles (101.65 mph) and four-day (101.17 mph) average speed records.

But Montlhéry’s bumpy surface had taken its toll on the car and just after the 10k-mile record had been reached, a rear spring snapped in half. Since a lengthy pit was required to fit a new one, the official records – other than timing – were halted. The team, though, were determined to complete the full seven days and so the run continued.

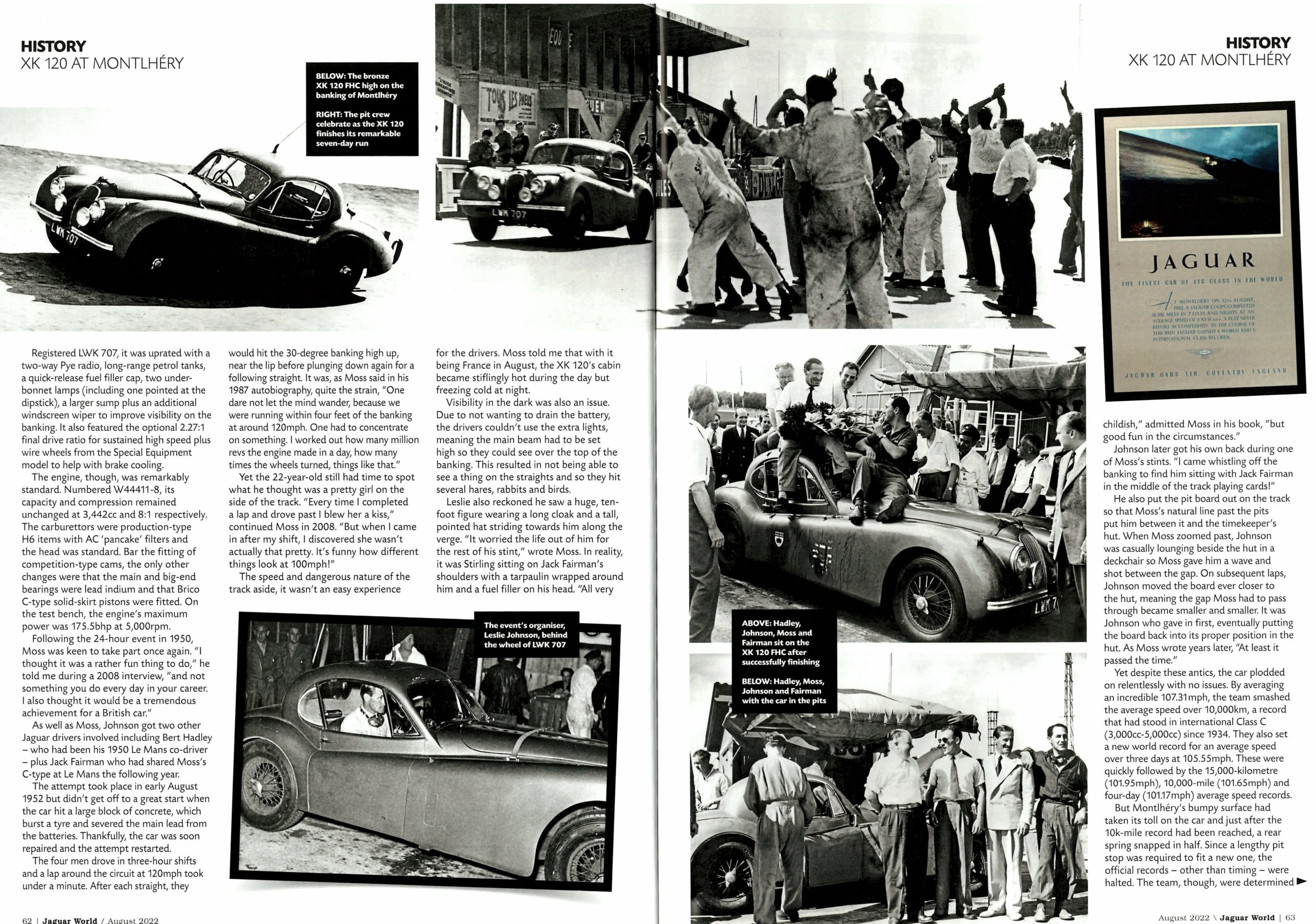

When the quartet finished three days later, they had covered an astonishing 16,851.73 miles at an average of 100.31 mph. “How many cars could you take of the showroom and ask to do that?” reflected Moss in 2008.

Even more amazingly, the bronze XK120 was driven back to the UK by The Motor magazine’s respected technical editor, Laurence Pomeroy, who discovered the marathon hadn’t affected the car. “After the event, there was no slack in the steering, no shake of the body, the brakes appeared to have full efficiency and they were in perfect adjustment.”

Following a whirlwind of publicity events, LWK 707 was retired from active service and although retained by the company, spent many years on display at Birmingham’s Science Museum. In 1983, the bronze coupe became part of the Jaguar Heritage’s collection of important cars and for the next 25 years remained in the same physical condition as when it left Montlhéry for the final time.

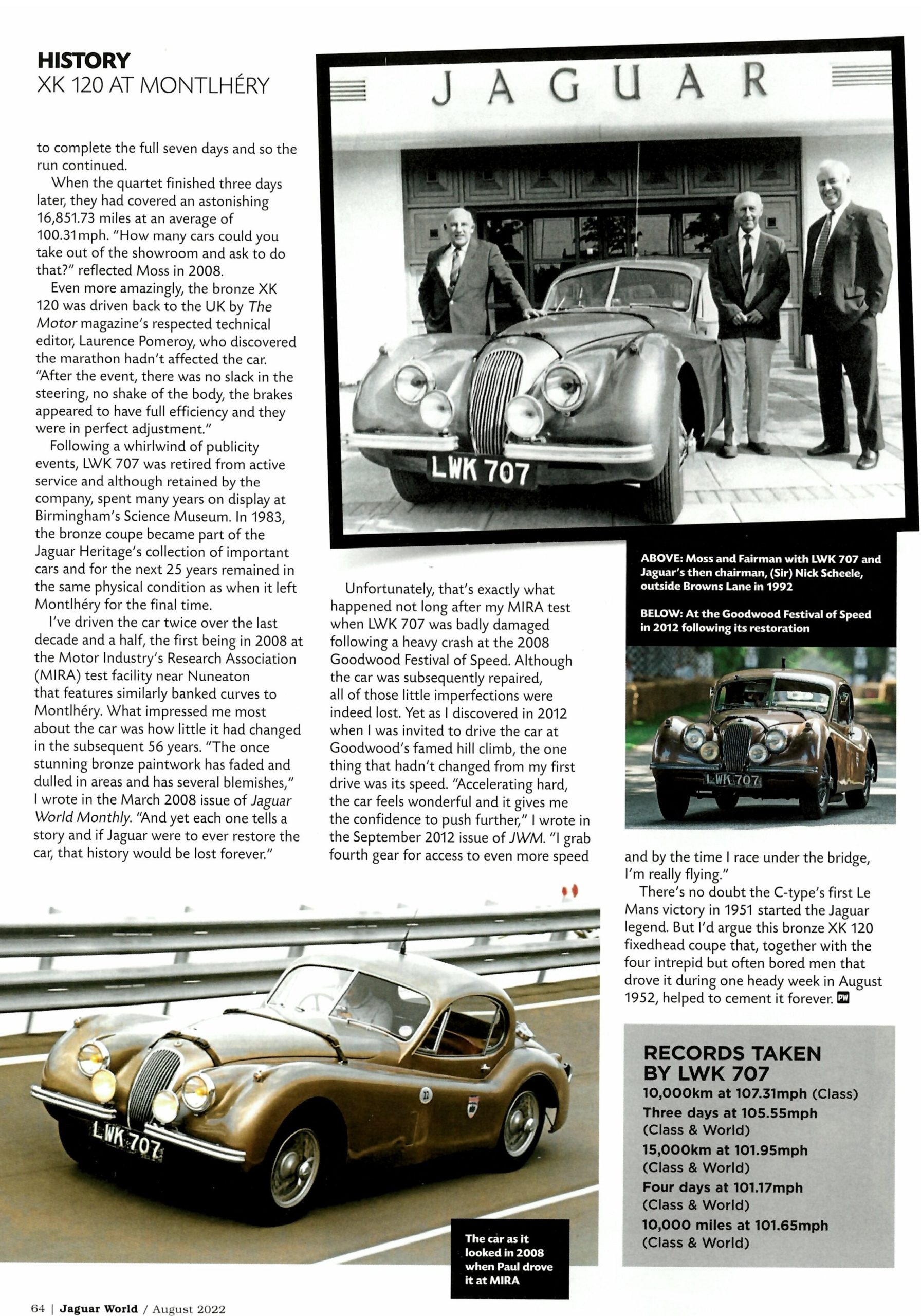

I’ve driven the car twice over the last decade and a half, the first being in 2008 at the Motor Industry’s Research Association (MIRA) test facility near Nuneaton that features similarly banked curves to Montlhéry. What impressed me most about the car was how little it had changed in the subsequent 56 years. “The once stunning bronze paintwork has faded and dulled in areas and has several blemishes,” I wrote in the March 2008 issue of Jaguar World Monthly. “And yet each one tells a story and if Jaguar were to ever restore the car, that history would be lost forever.

Unfortunately, that’s exactly what happened not long after my MIRA test when LWK 707 was badly damaged following a heavy crash at the 2008 Goodwood Festival of Speed. Although the car was subsequently repaired, all of those little imperfections were indeed lost.

Yet as I discovered in 2012 when I was invited to drive the car at Goodwood’s famed hill climb, the one thing that hadn’t changed from my first drive was its speed. “Accelerating hard, the car feels wonderful and it gives me the confidence to push further,” I wrote in the September 2012 issue of JWM. “I grab fourth gear for access to even more speed and by the time I race under the bridge, I’m really flying.”

There’s no doubt the C-type’s first Le Mans victory in 1951 started the Jaguar legend. But I’d argue this bronze XK120 fixedhead coupe that, together with the four intrepid but often bored men that drove it during one heady week in August 1952, helped to cement it forever.

RECORDS TAKEN BY LWK 707

10,000 km at 107.31 mph (Class)

Three days at 105.55 mph (Class & World)

15,000 km at 101.95 mph (Class & World)

Four days at 101.17 mph (Class & World)

10,000 miles at 101.65 mph (Class & World)